Lee Krasner was an important American abstract painter in the 1950s and 1960s. She was a pioneer in the synthesis of abstract form and psychological content that was the foundation of Abstract Expressionism. Her finest works combine all-over compositional structures with formal rhythms and subtle color harmonies. Her paintings are technically accomplished, emotionally powerful, and distinctly innovative.

Lee was "rediscovered" by feminist art historians during the 1970s and lived to see a greater recognition of her art and career, which continues to grow to this day. She is one of the few women to be featured in a full retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art.

Background: Lee was born in Brooklyn, New York to Russian-Jewish immigrants who fled to the U.S. to escape anti-Semitism. She was the 6th of 7 children. She was born Lena Krassner, but changed her name several times, finally settling on Lee—which is gender neutral—and Krasner, with one s.

Lee's parents operated a produce store. Her family lived a traditionally observant Jewish life, and the children attended Hebrew school as a supplement to public education.

Training: From an early age, Krasner knew she wanted to pursue art as a career. She enrolled at Washington Irving High School for Girls because they offered an art major.

|

| Self-portrait, c. 1930, age 22 |

Later she trained at the National Academy of Design, completing her course there in 1932, when she was 24.

At the age of 29, in 1937, after she had been working for several years, she began taking classes from Hans Hofmann; she studied with him until 1940. He emphasized the two-dimensional nature of the picture plane and using color to create spatial illusion. This is when she developed her "all-over" style, covering the surfaces of her paintings with abstract, repetitive designs.

Private life: While she was at the National Academy of Design, Lee fell in love with a dashing fellow student named Igor Pantuhoff. He was a Russian aristocrat who later became a successful society portrait artist. They say he began to style her in glamorous clothing and exotic jewelry. The two lived together for two years, and both worked for the Public Works of Art Project of the federal government. She was devastated by unannounced his departure.

In the 1930s and 1940s, there was a sort of mystique among women of devoting themselves to the support of a great male artist. Several women artists felt a conflict between the desire to nurture their partner's talent and the drive to develop their own careers.

Around 1940, when Lee first started having works in major exhibitions in New York, she met Jackson Pollock, a gifted abstract expressionist painter, 3 years younger than she, whose work was shown in the same exhibits. Lee was fascinated by Jackson's painting style and felt she could learn something from him. At the same time, he was much less sophisticated, having been brought up in rural Arizona and California. He was also less disciplined, and he struggled with alcoholism. It seems likely that she thought she could help him realize his talent.

Lee moved in with Jackson in 1941, and they began to learn from each other. In order to draw Jackson out of the heavy-drinking milieu of New York City, in 1945, Lee persuaded him to move with her to the village of Springs in outskirts of East Hampton, a remote location at the end of Long Island. That year they got married in a small ceremony. They fixed up an old farmhouse and outfitted a studio for each of them. They got into all sorts of domestic activities and entertained friends.

Jackson did manage to stay fairly sober for a number of years and worked on his painting with devotion. Around 1949, he made a major breakthrough and produced canvases that shook the art world. So, in a way, Lee accomplished her mission with Jackson. However, by 1955, he had resumed drinking heavily, and he had a flamboyant extramarital affair with an artist named Ruth Kligman. By 1956, Lee was discouraged, and made a trip to Europe, her first, to consider her options.

While she was gone, Jackson drunkenly plowed his car into a tree, killing himself and a woman passenger, and seriously injuring Ruth Kligman, who survived. Lee returned home. For the rest of her life she promoted Pollock's art and worked to ensure his legacy, while continuing to develop her own work.

By 1962, Lee had established a residence in Manhattan, but continued to spend several months a year in Springs, where she had moved into Pollock's old studio. In 1962, Lee had a brain aneurism that halted her work for a few years.

Lee died at the age of 75 after a period of ill health.

Career: In 1934, a couple of years after she finished her course work at the National Academy of Design, Lee began working for the WPA, a visual arts program sponsored by the government.

She began to exhibit in 1940 with the American Abstract Artists group. Soon after this, her work was shown in an exhibit that included major American artists with major European artists, such as her heroes, Matisse and Picasso.

Lee's career development was somewhat sidetracked by her marriage to an alcoholic artist named Jackson Pollock. During her marriage to Jackson, she took on the duties of promoting and managing his career, to the neglect of her own. She didn't stop painting, but she pushed his work instead of her own.

Pollock also affected her painting style. While her work was carefully controlled and deliberate, his was gestural and expressive. His style was trendier, and she wanted to develop in that direction. This caused her to enter a period of transition in which she didn't produce much work that satisfied her.

However, she made a breakthrough when she was about 38. Between 1946 and 1950, she produced 31 paintings known as the Little Image Series. These are her first all-over abstractions, demonstrating the expressive power of small, intricate lines and gestures. She worked looking down on her canvas, dripping paint to create tight figures in rows and columns. The painting's overlapping skeins of white paint form tightly controlled small units that shimmer on the painting's surface.

In 1951, Lee started her first series of collage paintings. Placing the support on the floor, she would

arrange scraps of old canvases, pinning them in place to determine the composition. She would then paste them down and add color with a brush, if required. It is thought she was inspired by the collages of Matisse's late career.

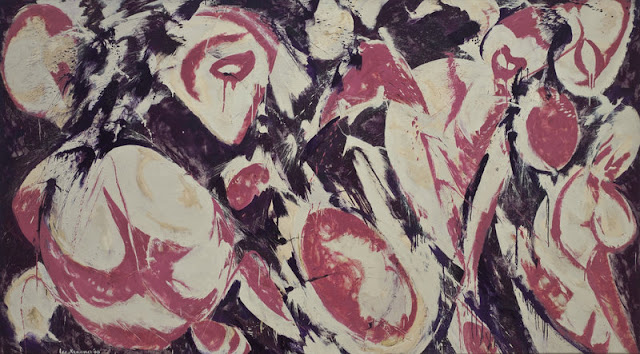

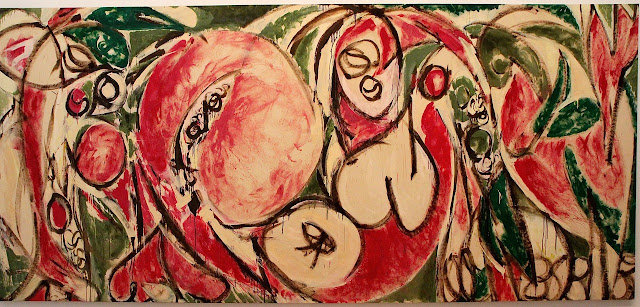

In the mid-1950s Lee started painting lush, biomorphic compositions of abstract, natural forms. After her husband died in a car wreck, she took over his studio, which enabled her to make very large works. Grand, sweeping gestures and simplified color palettes appeared in her compositions. She worked in this powerful new style for about 6 years. The first series was called Earth Green; it featured a combination of red, green and tan against a white background.

In the 1970s Lee's work took a new direction. She began painting flattened, hard-edged abstractions. Her color palette also simplified, and the paintings feel bright and optimistic.

Our photos of Lee's work:

|

| Composition, 1949 Philadelphia / Jan's photo |

|

| Milkweed, 1955 Albright-Knox / Jan's photo, 2012 |

|

| Desert Moon, 1955 LACMA / Jan's photo, 2017 |

|

| The Seasons, 1957 Oil and house paint on canvas (93" tall x 204" wide) Whitney Photo by Dan L. Smith, 2015 |

|

| Polar Stampede, 1960 SFMOMA / Jan's photo |

|

| Cobalt Night, 1962 National Gallery / Jan's photo |

|

| Night Creatures, 1965 Metropolitan / Internet |