According to a critic for The New Yorker, Peter Schjeldahl Agnes synthesized the essences of two world-changing movements—Abstract Expressionism and minimalism in her grids. Her response to a life tortured by schizophrenia was to derive a philosophy, amounting almost to a gospel, of happiness. There is nothing cuddly about Martin, but there is joy.

Background: Agnes was born in Saskatchewan, the third of 4 children. Agnes's father died when she was 3, and her mother moved the children to life with her widowed father a few hours away. When Agnes was 7, the family moved to Vancouver, where her mother supported the family by buying, renovating, and reselling houses. As an adolescent, during the early days of the Depression, Martin moved to Bellingham, WA, to help care for a pregnant sister. Although she spent the rest of her life in the States, she didn't become a naturalized citizen until 1952, when she was 40.

Training: Agnes didn't have the idea of being an artist when she was young. Instead, she trained to be a teacher at a college in Bellingham, and she taught in various public schools in Washington.

At the age of 29, in 1941, she attended Columbia University's Teachers College, where she studied arts and arts education. About this time she decided to be an artist herself.

In 1946 she began studying art at the University of New Mexico, and returned to Columbia in 1951 to earn a master's degree in fine-arts education. She also began to study Zen Buddhism.

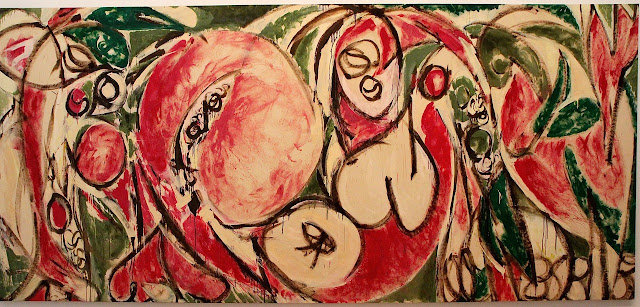

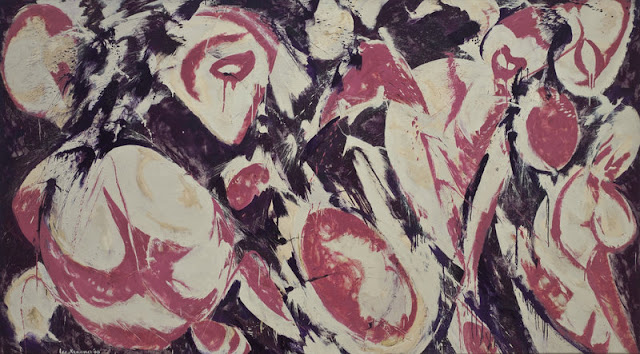

Career: After finishing her masters, Agnes spent a few years doing odd jobs in New York while painting portraits and landscapes. Later she moved on to abstract paintings of organic forms. These works received attention as part of the minimalist movement. She spent about 10 years trying various styles and techniques. Eventually her thinking led her to produce images based on small-celled grids.

When she was about 55, Agnes began having psychotic episodes resulting in several hospital stays. She left New York, and after a year's roaming about the U.S., settled in New Mexico. For the next few years she devoted most of her energy to building her own primitive dwelling, first in one location and then in another.

When she was satisfied with her house, Agnes felt truly at home in New Mexico, and in 1971, when she was 59, she embarked on two highly-productive decades in which she created her most important work. She isolated herself from social interaction, practiced a meditative life-style, and devoted herself completely to making art that was serene and joyous.

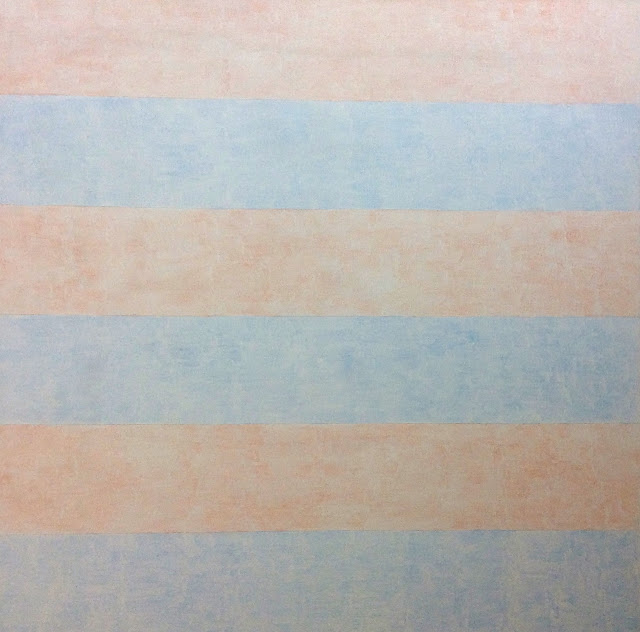

Her new work moved on from the grid to horizontal bands and lines, rendered in pale colors and delicate graphite. She felt that a horizontal line expressed perfection and harmony, and her horizontally banded paintings evoke the flat, warm earth, the jewel-blue sky, and the benign sunshine of New Mexico.

For the rest of her life, Agnes showed in one exhibit after another, sales increased, and her work received increasing critical regard.

Private life: As a child, Agnes believed that her mother hated her and that she liked seeing people hurt.

As an adult, Agnes tended to be solitary. During the years when she was getting her education, she moved back and forth between New York and New Mexico, and worked odd jobs to support herself, which kept her from forming long-term relationships.

In the late 1950s her dealer got her to settle in an artists' neighborhood in lower Manhattan, which was the home of several gay and lesbian artists. She felt comfortable in this liberal environment, and she was known to have lesbian relationships with a textile artist and a sculptor. However, when she was in her 50s, Agnes began to have psychotic episodes that included auditory hallucinations and catatonic trances, and she was hospitalized repeatedly, even receiving shock therapy. Her illness made her even more committed to solitude.

In 1967, having lost the lease on her studio in New York and received a grant large enough to buy a truck and airstream trailer, she ditched her possessions and left New York for an extended road trip. After 18 months of roaming, she settled in a small town in New Mexico in 1968. For a few years she was occupied with building her own dwelling, moving, and building another dwelling.

Her years in New Mexico were marked by a profound withdrawal from worldly things, a life of renunciation and restriction that often sounds punishingly masochistic, though Martin insisted the intention was spiritual, an ongoing war against the sin of pride. The voices were strict in their limitations. She wasn’t allowed to buy records, own a television, or have a dog or cat for company.

Her reclusiveness and her spartan existence contributed to her growing status as the desert mystic of minimalism.

As she aged, Martin became happier and more social, as well as considerably more wealthy. In 1992, she moved into a retirement community in Taos, New Mexico, driving each day to her studio in a spotless white BMW, one of the few extravagances in a life still dedicated to extreme material simplicity. When she died at the age of 92. It was said that she hadn't read a newspaper for 50 years.

|

| Photo by Annie Leibovitz |

My photos

|

| Leaf in the Wind, 1963 Norton Simon / Jan's photo, 2017 |

|

| Night Sea, 1963 SFMOMA / Jan's photo |

|

| Drift of Summer, 1965 SFMOMA / Jan's photo |

|

| The Cliff, 1967 LACMA / Jan's photo, 2017 |

|

| Untitled #21, 1980 Anderson Collection / Jan's photo |

|

| Untitled #6, 1980 SFMOMA / Jan's photo |